By Lesley Greenwood [E.2.7a.3b.9c.1d]. Originally published in HAFS Journal Vol 16 No 3, May 2022. For Part 1 see HAFS Journal Vol 16 No 2, Nov 2021.

Introduction

The Hungerford & Associated Families Society (HAFS) has, over the past three decades, accumulated a massive amount of information, providing a comprehensive family history and an extensive Hungerford family tree.

Utilising information compiled in the Hungerfords Down Under (HDU) database (2020), it has been possible to derive some demographic statistics pertaining to the eight generations of the ‘E’ line of Hungerfords since arriving in Australia in 1828 (a ninth generation has one known member).

In Part I, a history of births, fertility rates and family size was analysed: see HAFS Journal Vol 16, No 2, pp13-20. This second Part deals with some aspects associated with death – life expectancy, infant mortality, gender ratios and age structure. A third article, on marriage, is proposed to complete this demographic trilogy in a later Journal.

Death is a topic of conversation that most people prefer to avoid but it is nevertheless an inevitable event. From a demographic perspective, mortality statistics are both intriguing and useful in providing information on the health and well-being of populations, as well as on the nature of the times in which people lived.

They are also, for quite pragmatic purposes, of particular interest to retirement planners, and longevity risk managers in calculating, for example, anticipated future pension and superannuation needs and insurance liabilities.

Methodology

The HDU database contains Hungerford family records, including, where known and applicable, dates of death and ages of deceased relatives. Given that each successive generation of the family spreads across increasing periods of time, now stretching over more than 100 years between the first- and last-born of more recent generations, and due to overlapping generations, this analysis uses age or date groupings for comparison purposes.

Data were also split by gender to demonstrate the differences in age structure for males and females. The information is then presented as a population pyramid to graphically illustrate life expectancy and longevity. It is assumed that the HDU database, while acknowledging that it is not totally complete, is sufficiently comprehensive and reliable for statistical analysis. For example, assumptions have had to be made in the few cases where there is no known date of death for ancestors born prior to 1915 and the number of living older relatives may be overstated if such information is missing for some recently deceased family members. There is also a concerningly low number of known more recent members.

Results

Overall, the ‘E’ line of the Hungerford family would appear to be very healthy, with greater longevity than the Australian population in general. In Part I, it was indicated that there were around 5,500 known direct descendants of Catherine and Emanuel Hungerford. In 2020, there were more than 4,500 of us still living and breathing, that is, over 80% of Catherine and Emanuel Hungerford’s direct descendants are alive today.

These living descendants comprise representation from seven generations of the Hungerfords, ‘b’ to ‘h’, ranging from Catherine and Emanuel’s great-grandson [E.6.16a.6b] to their 7 x great-granddaughter (on the E.1.1a.2b line). Descendants’ ages range from over 100 years old to newborns.

Life expectancy

Death rates in Australia have been declining since the beginning of the 20th century. They have been higher for males than for females but improvements in medical factors (surgery, care, diagnosis and medicine), lifestyle modifications (smoking, diet and blood pressure management) and safety considerations (road and workplace safety, vehicle advancements and less global conflict) have lowered rates for both genders and reduced the difference between genders. The result is that life expectancy has increased.

Life expectancy can be defined as the mean (average) age at death. For the ‘E’ line of the Hungerford family, it is possible to measure the successive increase in life expectancy for those that have lived through a natural lifespan. Table 1 (see below) indicates the increasing longevity of earlier-born Hungerfords. There are still surviving members of those born in the 1920s (in the 92-102 year old age group) so the life expectancy measure for that group, and those born subsequently, is unable to be calculated.

The Hungerford family compares very favourably against Australian life expectancy tables. For those born in the 1900s decade, life expectancy in Australia was around 50 years old; for Hungerfords born then, their average was 72 years old (as illustrated in Table 1 below).

The forecasting of life expectancy is based on an estimate of the average age that members of a particular population group will be when they die. Life expectancy for Australians born today is 81 years for males and 85 years for females.

Table 1 – Life expectancy of Hungerford ‘E’ line ancestors

| Year born | Num of Hungerfords | Average age at death (years) |

| 1800-1819 | 4 | 63 |

| 1820-1839 | 15 | 66 |

| 1840-1859 | 49 | 71 |

| 1860-1879* | 91 | 65 |

| 1880-1899* | 196 | 68 |

| 1900-1919 | 298 | 72 |

It is also possible to gain some understanding of current life expectancy by comparing recent death statistics for Australia and for the ‘E’ line of the Hungerfords (refer to Table 2 below). On every measure, the Hungerford family has greater longevity than the general population.

Table 2 – Life expectancy comparison

| Feature | Australia 2019 | Hungerfords 2010-2019* |

| Number of deaths | 169,301 | 92 |

| % deceased males aged 75 and over | 59% | 79% |

| % deceased females aged 75 and over | 73% | 86% |

| Median age at death – male** | 78yo** | 86yo |

| Median age at death – female** | 84yo | 90yo |

** The median is the middle number when ages are ranked from lowest to highest. For example, of the men who died in Australia in 2019, half of them were more than 78 years old and half were younger than 78 years old.

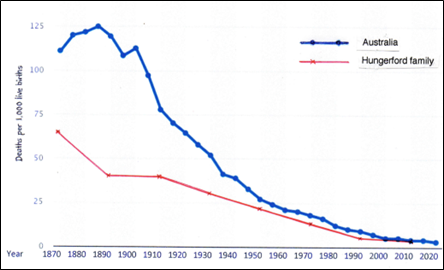

Infant mortality

Of the almost 1,000 direct Hungerford ‘E’ line descendants who have passed away, 83 were identified as infant mortalities (infants who died before their first birthday). Historical infant mortality rates for Australia were as high as 125 infants per 1,000 live births in the 1880s. Since that time, improvements in health and safety and advances in medical technology have dramatically lowered the rate. The current infant mortality rate for Australia is around 2.8 infant deaths per 1,000 live births.

A comparison of historical trends for Australia as a whole and for the ‘E’ line of the Hungerfords illustrates that earlier Hungerford pioneer babies were more robust than the then general population and, since post-WWII, have been reflective of the rates for the national population (see Graph 1 below).

Graph 1 – Infant mortality comparison of Hungerford ‘E’ line to Australian population 1870-2020

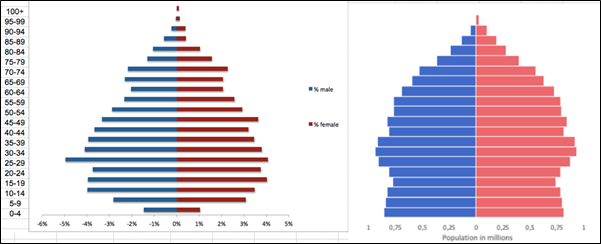

Age structure

In the past, higher infant and child mortality rates would have the effect of gradually evening out the ratio of males to females. Typically, more males are born than females, so the ratio at birth has been to favour, and still is favouring, more males. For instance, of registered births in Australia 2018, 51.4% were males, resulting in a sex ratio at birth of 105.9 male births per 100 female births. The gender gap tends to dissipate in the early ages and by around the mid-30s ages, there are then more females than males. In Australia, total population in 2020 was 99.2 males per 100 females (ie 49.8% males to 50.2% females).

However, amongst the Hungerfords, low rates of young male mortality have sustained the high numbers of males and, as illustrated in the Hungerford ‘E’ line population pyramid (see Graph 2 below), there were still more males than females in the total living Hungerford population (51.0% males to 49% females) in 2020, although more females are outliving their male nonagenarian counterparts.

It is important to comment on the low numbers of known relatives in the very young age groups on the Hungerford population pyramid, which is evident when compared to the Australian data. This may (or may not) be largely indicative of under-reporting on recent Hungerford births due to loss of contact with some branches of the family.

The possible lack of complete data here skews the proportions in other age groups (by over-representing them) but does so proportionally. The shape of the Hungerford population pyramid for the older age groups is considered reflective of the actual age structure of the Hungerford family (on the basis that HAFS has comprehensive historical records for these members).

In all probability, the actual proportions of younger Hungerford age groups would be anticipated to mirror the national pattern, which displays a trend of lower numbers in both genders since the late 20th century. The ‘bulge’ of the age groups 25-39 years illustrated in Graph 2 is the ‘echo’ effect, that is, the children of post-WWII baby ‘boomers’, whose ‘bulge’ in the 65-74 age groups is still visibly apparent in the Hungerford population.

Graph 2 – Population pyramid of the Hungerford ‘E’ line compared to Australia, 2020

Further comments

On a whim, further analysis was undertaken to test the hypothesis that there is a seasonality to deaths. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare calculated that, in Australia, there are more deaths in winter (June, July and August) and fewer deaths in summer (December, January and February). There was a slight, but statistically insignificant, tendency apparent in this pattern in the Hungerford family.

A more interesting, if somewhat unnerving, revelation was that Hungerfords were almost twice as likely to die within a fortnight on either side of their birthday than at any other time during the year. Analysing a representative sample of 400 Hungerford deaths, it was found that 15.75% died within the period of 15 days either before or after their birthday. Statistically, it would be anticipated that deaths would be evenly distributed across every day of the year, meaning that this should occur at the rate of 8.21% per 30-day month.

This phenomenon has been scientifically documented in other studies and is known as the ‘birthday effect’. Some of this coincidence may be attributed to psychological factors but there are numerous other reasons, in isolation and in combination, that could account for such a result. If concerned, keep in mind that “the past is not necessarily going to predict the future”.

Despite the sombre subject matter, Hungerfords can take heart that, in the family, mortality issues have generally indicated a healthy, enduring population.

However, life is for living – so let’s get on with it!

References:

Australian Bureau of Statistics: abs.gov.au/statistics – various

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: aihw.gov.au/reports

Macrotrends: https://www.macrotrends.net

Statista: statista.com

Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org