Athol Gordon Townley ~ 1905-1963

This article, by Lesley Greenwood [E.2.7a.3b.9c.1d] was first published in HAFS Journal Vol 16 No 1, May 2021.

Athol Townley [E.2.7a.1b.3c=] described himself as “a pretty ordinary kind of bloke”. His demeanor may also have belied this image. In fact, despite his self-deprecation, he was quite extraordinary and led an, at times, exciting and successful life that could have been out of the pages of a Boy’s Own adventure – successful sportsman, pharmacist, naval commander, licenced pilot and federal politician.

Except that in real life, adventure is interspersed with mundanities, tough luck and having to make difficult, adult decisions, often between complex and conflicting factors – even more so when one carries the responsibility for others, requiring the firmness of one’s convictions and the selfless giving of heart and soul. Even during his last few years of ill health, Athol Townley remained courageously dedicated to his work, including travelling overseas to complete critical government business.

Humble beginnings

It is also insightful to write about Athol Townley’s family. His sad family circumstances during his childhood, and his strong religious beliefs, were influential in shaping his views, while his close connections with his family were intertwined throughout his whole life.

Athol was born in Hobart, Tasmania on 3 October 1905, the last of four children born to Reginald George Townley and Susan McGinnity (‘Susie’) Townley (née Bickford). He had two sisters: Lillian Alma Townley, the eldest child, was born in 1899. The other sister, Margaret Louisa (‘Madge’) Townley, he never knew: she died when only 19 months old in May 1903. Athol also had an older brother, Reginald Colin (‘Rex’) Townley, born on 5 April 1904.

Athol’s father, Reginald, was a clerk in an accountancy firm. He was also a sapper in the Corps of Australian Engineers, one of the voluntary military forces established by the Tasmanian Government in 1883 to defend the colony. The Corps’ work involved submarine mining operations in the Derwent and Tamar rivers, bridging and elementary fortifications and field telegraphy. It had a beleaguered history, being reliant on government funding that limited the extent of its activities. In 1902 the various Corps were amalgamated, following Tasmania’s defence forces being transferred to the newly-formed Commonwealth of Australia.

Tragedy again struck the young family when Reginald died suddenly on 12 August 1906 from heart disease, leaving his wife a widow with three children aged seven years, 2½ years and 10 months old. The family subsequently moved in with Susie’s sister Rebecca Mabel Sidwell (née Bickford) and her husband Harry Sidwell, above the chemist shop in Elizabeth Street, Hobart, in which Harry had a partnership.

The Sidwell and Townley families were prominent members of the Hobart Baptist Church. In particular, Susie was recognised as a “godly mother [with a] force of character and sanctified commonsense”, Harry was Treasurer for 30 years, and Rex and Athol held numerous church positions throughout their adult lives.

Brothers in learning

Athol and his older brother Rex both attended the local Elizabeth Street State School, then went on to Hobart High School and Hobart Technical College, as well as studying chemistry subjects through the University of Tasmania. They were both keen sportsmen, playing Australian Rules football for North Hobart and cricket for New Town. Rex’s ‘claim to fame’ was that in 1936, when playing for the Tasmanian State Team, he took the wicket of one Donald Bradman in a match against South Australia.

Both brothers qualified as pharmaceutical chemists about the same time, serving apprenticeships in their uncle Harry’s pharmacy of Ash, Sidwell and Co in the late 1920s. Both moved to Sydney for a time. Rex returned to Hobart in 1930, where he and his uncle Harry established the pharmacy Sidwell & Townley.

In 1930, Athol, still in Sydney, was employed as an analytical chemist to look after quality control at Gartrell White Ltd, at the time the largest bakery in Australia. The company later merged with Golden Crust Bakery of Adelaide to eventually become Tip Top Bakeries, now owned by George Weston Foods, a subsidiary of multinational Associated British Foods.

Athol and Hazel

Athol’s time in Sydney was well spent. It was there that he met, and married, Hazel Florence Greenwood [E.2.7a.1b.3c] at the Baptist Church in Dulwich Hill on 26 December 1931.

Hazel was the third of four daughters born to Oliver Youell Greenwood and Charlotte Florence Johanna Greenwood (née Myers). Hazel and her sisters had spent their formative years in north-western NSW, where their father was a teacher at Ashley Public School.

The couple moved to Hobart in 1935, and Athol joined Rex and Harry in partnership at Sidwell & Townley. Athol eventually went on to become general manager of the firm: in all, they owned three pharmacies in Hobart, including one in the CBD.

In 1939, Hazel and Athol’s only child, Athol David Townley [E.2.7a.1b.3c.1d], was born. Athol (Snr) added ‘devoted father’ to his list of attributes, although the war, and later, politics, would impose an away-from-home parenting role involving long absences and long distances.

War-time experiences

Also in 1939, on 3 September, Prime Minister Robert Menzies[1] announced that, as Great Britain had declared war with Germany, so too was Australia. Athol joined the Royal Australian Naval Volunteer Reserve in September 1940 as a probationary sub-Lieutenant, and was soon mobilised to Sussex, England.

Athol’s wartime experiences were not without danger and drama. In 1941 he was participating in hazardous bomb- and mine-disposal work, ‘delousing’ (defusing) unexploded German mines around the London Docks and the Thames River. On 1 June 1942, back in Australia, he was captain of the patrol boat, Steady Hour, that assisted in destroying one of the three Japanese midget submarines that penetrated Sydney Harbour.

In 1943, as A/Lieutenant, he was the first commander of the new, highly manoeuvrable Fairmile Motor Launch 817, conducting anti-submarine patrols and coastal surveillance in Papua. In September 1943, in New Guinea, after being attacked by Japanese aircraft, he nursed his heavily bomb-damaged Fairmile and crew to safety. As Lieutenant Commander, he was later in charge of a flotilla of Fairmiles. He was demobilised on 25 June 1945, but remained with the naval reserve until 1955, retiring as Honorary Commander.

After the war, Athol resumed civilian life as a chemist in Hobart. He also contributed to civic-minded efforts, for example being appointed as a director on the Commonwealth’s Repatriation Board in 1947 for 18 months.

MP for Denison

Although he initially had Labor Party sympathies, Athol was opposed to bank nationalisation. In late 1949, he became the Liberal Party’s candidate for Denison in the December federal election. A re-badged Robert Menzies, now as leader of the Liberal Party,[2] in coalition with the Country Party, won government.

Athol’s broad appeal and popularity amongst the local community, through his business, welfare and church interests, catapulted him into winning the seat. From then on, Athol won his seat at the next six elections, was elevated into the Ministry in 1951 and thereafter held seven successive ministerial portfolios.

Athol had the enviable patronage of Robert Menzies (left), Prime Minister of Australia throughout Athol’s tenure in office. Menzies possibly saw a kindred spirit in Athol Townley. He valued his counsel and political judgement, perhaps in part because the two men came from similar humble backgrounds and shared similar views. They were both adamant that Australia was British in character and behaviour, and they were both vehemently opposed to communism.

Cabinet career, 1951-1958

Athol was first appointed to Cabinet as Minister for Social Services in May 1951. Having experienced compassion in his early upbringing and through his church, he was sympathetic towards the disadvantaged. Under his watch, pensioners became better off. In 1954, he was responsible for removing the means test on pensions for the blind, an exemption anomaly that remains today.

Trade unions were also viewed sympathetically: he was never as rigid in his attitude to them as were many of his future Liberal Party colleagues. In a notable 1950 political speech he reminded employers that in their drive for profit they should remember that their employees were “human beings who possessed human dignity”.

Athol was suitably qualified as Minister for Air and Minister for Civil Aviation, positions he held following the mid1954 election until late 1956. He had developed a personal interest in aviation and was actively involved in assessing advances in airline technology.

As a member of the Aero Club of Southern Tasmania, he became an aircraft pilot, obtaining flying qualifications for small planes to commercial jets and for helicopters.

He regularly flew himself, sometimes accompanied by his family, between Hobart and Canberra, elsewhere within Australia, and to New Zealand.

Minister for Immigration

In the next Menzies ministry, Athol was elevated to Minister of Immigration, from late 1956 to March 1958. During that time, he launched the government’s ‘Bring Out A Briton’ propaganda campaign.

“Australia is a British Country…The great majority of native-born Australians are the descendants of British stock,” Townley proclaimed in 1957.

The campaign was designed to strengthen British culture in Australia, and to counter anxiety about the increasingly high proportion of non-British European emigrants. Local community committees were to identify employment opportunities and suitable accommodation, and the government would then facilitate fulfilling the migration needs.

Following the Liberal’s election win in February 1958, Athol Townley, now an experienced politician, was given the portfolios of Defence Production and Supply, and later that year, Defence. He held the Defence ministry for the next five years.

Flying the Mirage

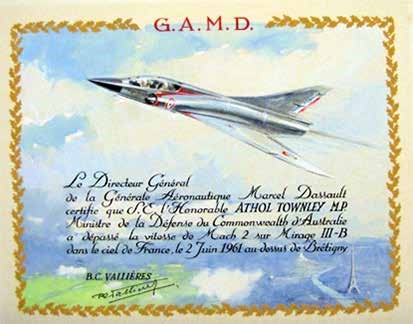

On an official visit to Europe and Britain in 1961, Athol Townley was able to combine his passion for aviation with his ministerial portfolio responsibilities. On 2 June, no doubt applying the ‘test-it-yourself’ principle, he flew a Dessault Mirage III-B at Mach 2 across the skies of France. It was one of his greatest thrills.

The Director-General of Generale Aeronautique Marcel Dassault certifies that he the Honorable ATHOL TOWNLEY, MP Minister for Defence of the Commonwealth of Australia, exceeded the speed of Mach 2 in the Mirage III-B in French skies on 2 June 1961 over Bretigny. [Signed] B C Vallieres.

The Menzies government was looking for a new fixed wing, lightweight striker, and RAAF personnel in 1959 had recommended the French Mirage jet aircraft. Australia purchased more than 100 of them and they began service in 1965.

There were at least two more significant, not-unrelated, political issues occupying Athol’s time – the need to also replace the RAAF’s aging fleet of aircraft known as ‘Canberras’, and the worsening threat of Communist infiltration in South East Asia, in Laos and Cambodia but most notably in Vietnam.

The Vietnam War

Athol drew the line at the inherent goodness of people and society when it came to Communists: “I find it difficult to see how we can extend the orthodox and normal processes of the law to Communists,” a view that he held in keeping with Menzies.

“We are going to declare war on the Communists, we are going to give them a thrashing”, Menzies had stated in the 1949 election campaign. The Australian Communist Party was duly banned in Australia in 1950 but the government’s decision was overturned following a High Court challenge and subsequent referendum. The ban did not, however, stop the poor treatment and denial of Australian citizenship of suspected individuals, especially some European migrants.

The government’s mindset of opposition to local Communism also extended overseas. The thinking was that if one country fell to Communism, it would signal a ‘domino effect’ that would spread to other South-East Asian countries, and even threaten the security of Australia.

In 1962, Athol Townley, as Minister for Defence, sent a non-combat team of thirty Special Forces military training advisers to the Republic of (South) Vietnam, a political decision – but nonetheless a possibly partisan and inevitable one – that signaled Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War.

Although it had been simmering since 1955, the war intensified in the mid1960s, by then including battalions from Australia. It was bitter, controversial and divisive, both at home and abroad. In the end, South Vietnam unified with North Vietnam under Communist rule in 1975 (as would Laos and Cambodia), but not before a human death toll numbering in the millions.

The F-111

Another significant moment for the Government in 1963 was the decision to purchase new fighter aircraft. A general election had been called. Athol Townley was dispatched to Washington in October to finalise negotiations on an agreement on the TFX (later to become known as the F-111) so that the commitment could be announced during the campaign. The deal was considered advantageous to Australia at the time, with a set-price tag of US$125 million for 24 strike bombers, with aircraft loaned from the USA in the meantime.

The Liberals won the election, but the purchase contract (signed the next year) for the F-111s was later scathingly criticised as ‘flawed’, since other costs, relating to further research, technical difficulties, redesigns and delivery dates blew out. However, the F-111 did eventually become Australia’s principal strike aircraft from 1973 until 2010, somewhat vindicating the initial decision. Ironically, the F-111 never engaged in enemy combat throughout this time. It has since been replaced by the F/A-18F Super Hornet.

Athol never saw the outcome of his inceptive role in the Vietnam War or the furore over the F-111 aircraft’s escalating cost. During the early 1960s, he had suffered a heart attack and recurring pneumonia. Menzies, in a caring but firm personal letter, relieved him of duty for a couple of months in mid-1963 to recuperate.

A dedicated life

Ever dedicated, Athol had returned to work in July 1963, and again retained Denison at the 30 November election. But he collapsed in his office in Melbourne on 13 December and was hospitalised. Menzies announced the appointment of Athol Townley as Ambassador-designate to the United States of America. A few days later, however, on Christmas Eve 1963, Athol Townley died from a heart attack. He was given a State funeral.

Tasmania had never witnessed so large a funeral, with attendees including the Prime Minister and other political colleagues, members of the community and lifelong friends and family. The streets were lined with thousands of people who regarded him with obvious great affection and respect.

Athol Townley’s political legacies include contributing to improvements for disadvantaged groups, such as facilitating the humanitarian resettlement of refugees and better pension entitlements, and spearheading a rapid change to modern technology in the armed services.

Of course – as is the nature of politics – he was criticised by the Opposition and sections of the public for some of his political viewpoints and actions, and experienced some disgruntlement from within his own party. But none could doubt his sincerity and well-intentioned efforts.

Tributes to Athol Townley, both during his life and after his death, characterised him as a ‘quiet administrator’, friendly, unselfish, generous and trustworthy. He was considered an outstanding sportsman as well as a good sport. He displayed great integrity in business, and gave distinguished service beyond the line of duty. He had a dedication to hard work and a devotion to responsibilities entrusted to him. He was a man of warm-hearted and simple charm. International media reports were also very flattering, referring to him as ‘handsome’ and ‘future Prime Ministerial material’.

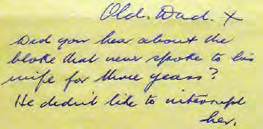

Townley possessed a light-hearted sense of humour. He would often tell jokes to his parliamentary colleagues, and he and Menzies shared an affable relationship that included a common appreciation for wry humour. In letters to his wife and son, he referred to himself as ‘Old Dad’.

Postscript to a letter from ‘Old Dad’ Athol to his son, Athol (junior): “Did you hear about the bloke that never spoke to his wife for three years? He didn’t like to interrupt her.”

Dated ‘Wednesday’ some time in 1951-53, when Athol was Minister for Social Services.

The Townley inheritance

The personal life of Athol Townley was characterised by family influences that have woven threads through the generations: taking after his father in his voluntary military commitment, taking after his uncle and brother in following a pharmaceutical career, taking after his brother in sporting prowess and politics. He inherited his mother’s strong work ethic, Christian faith and goodness.

Athol Townley was himself a role model who, in turn, influenced his own family: his nephew followed him into politics, his son and another nephew became pharmacists, his son was also a top cricketer and one of his grandsons is a commercial airline pilot.

The origin of each of us stems from codes of genetic inheritance.

Sir John Carew Eccles (1903-1997), Nobel Prize winner, December 1963.

References:

National Library of Australia archives, as copied by HAFS

National Archives of Australia, https://www.naa.gov.au/explore-collection/australias-prime-ministers/robert-menzies/during-office

Bennett, Scott, ‘Townley, Athol Gordon (1905-1963)’. Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 16 (Melbourne University Press, 2002)

wikipedia.org and other internet sources

Kristina Kukolja and Lindsey Arkley, www.wheelercentre.com/events/not-quite-australian-citizenship-and-belonging

Rowston, LF, ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF WITNESS: A History of the Hobart Baptist Church 1884-1984

Sir John Eccles, Banquet speech, 10 December 1963. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Media AB 2021 https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1963/eccles/speech/

Private conversations with Athol David Townley