by RB Winder and RH Prentice

[Editor: This article was originally published in three parts in HAFS Journals Vol 1 No 2, Vol 1 No 3 and Vol 1 No 4. Researchers should cite the Journal reference rather than this web page.]

Part 1 – The Voyages of 1814-1817

Birth and Background

The birth and family background of this person has been the subject of much conjecture, but as yet few facts have been established. Our family historian PD Sherlock, in his book Hungerfords of the Hunter says that he was born in 1787 or 1788, the son of Arthur Wesley (later Wellesley) and Lady Elizabeth Dundas of Edinburgh, Scotland. Sherlock says:

The Honourable Thomas White Melville Winder was, according to many different family traditions, the illegitimate son of Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington. When the Duke-to-be was 17, he joined the 73rd Highland Regiment in Scotland. During this time he met Lady Elizabeth Dundas, the former wife of Henry Dundas, Viscount Melville. Elizabeth was the daughter and heiress of David Rennie. She and Henry had been married 16 August 1765. They had four children, but were divorced for unknown reasons in 1779. Henry married again in 1793. Elizabeth may have remarried, but it seems unlikely.

Another researcher, with an interest in the Hungerford/Winder families, the late Mr Palgrave Carr, was of the view that TWM Winder may not been the son of Arthur Wellesley, but rather his nephew 1. Apparently one of Arthur Wellesley’s brothers did have an illegitimate child at the relevant date, and Arthur took a great interest in the child.

The first record of Tom Winder in the early colony of New South Wales which came to our notice concerns his life as Purser on the 443 ton convict ship Surrey, which arrived in Port Jackson on 20 December 1816 under very unusual circumstances for convict vessels in that period of history. To get a perspective on this incident, we should go back two years to the 1814 voyage of the Surrey and follow the story from there because the earlier voyage had an influence on the 1816 passage.

The 1814 Voyage of the Surrey

Late in the Northern Hemisphere winter, on 22 February 1814 the Surrey sailed from England under command of James Patterson, in company with another convict transport, heading for New South Wales. As was usual on such voyages, particularly during the early years of transportation, the convicts were allowed little freedom. They were kept below decks, chained in damp quarters with little fresh air. Their clothes, belongings and bedding went unaired for some weeks and even months during such voyages. If disease broke out the ship’s doctor had few medicines to treat the sick. Regular exercise, airing clothes and bedding could help; but unless the ship’s Master consented, such freedom was denied to the unfortunate passengers. In the case of the Surrey under Patterson, hours of freedom above deck were kept to a bare minimum.

Before Rio de Janeiro was reached a case of typhus was diagnosed among the convicts. A brief stop of ten days in this Brazilian port was insufficient to curb the outbreak, and soon after sailing from there the complaint spread rapidly among the convicts and eventually spread to crew members including the ship’s officers. Still the Master did nothing to alleviate the suffering of those confined below decks.

Arthur Bateson in his excellent book The Convict Ships gives a full account of this voyage and reports that by the time the vessel reached the coast of New South Wales, somewhere near where Nowra is now,2 the position was desperate. The Master, his officers, the surgeon and many others were dangerously ill. Control of the ship was impossible. Before the day was over, Captain James Patterson had died. In the year 1814 few vessels would ply this coastline; and yet the unusual can happen as it did on this occasion. The Bloxbornebury, the vessel which had sailed with the Surrey five months earlier, sailed close, and noting the position, came alongside and learned of the desperate plight of the ship and crew. A volunteer went aboard to guide the stricken Surrey to safe harbour, and on 27 July 1814 she entered Port Jackson where she was immediately quarantined. Tents were erected ashore down harbour from the small settlement and the occupants of the vessel remained there, until the disease worked out its grim toll. 3

The surviving senior officer was young Thomas Raine. The Governor promoted him to act as Master of the ship for her return voyage to England via China. She sailed out of Port Jackson on the 8 November 1814. Obviously the experience aboard the Surrey on her 1814 outward journey had a profound influence on the young Thomas Raine and on others. In due course the Surrey again reached England where her owners, the renowned shipping firm of Mangles of London confirmed the appointment of Thomas Raine as her Master, and in July 1816 she sailed from Cork, Ireland with 150 male convicts, a crew of 35 and a detachment of the 46th Regiment on her voyage to New South Wales.

The 1816 Voyage of the Surrey

Experience is a good teacher, it is said, and the experience of the former voyage must have influenced Captain Raine very deeply with the result that with him as Master there was to be an almost complete turnaround in the treatment of convicts on this voyage. It should not be assumed, however, that discipline aboard was to be in any way relaxed; but the approach of rewarding good behaviour with kindness, and punishing wrongdoing with limited punishment by confinement below decks achieved a most remarkable journey for all concerned, and particularly for the principally Irish convicts. These ‘government servants’ appreciated and honoured the kindness and trust shown to them on this voyage. They would undoubtedly have heard about the general treatment of convicts on former voyages, and quite probably learned from the crew of the former outward voyage of the ship. That knowledge would have helped to build their appreciation and encourage good conduct while on board. Endeavour was made to educate the largely illiterate prisoners.4 They were encouraged to exercise, to sing and make music. The voyage was pleasant an experience as was possible at the time and in the circumstances.

From Cork the Surrey sailed via Rio to Port Jackson where she arrived after a voyage lasting approximately five months. Her prisoners were in an excellent state of health and spirit. The Log of the Chief Officer of the Surrey, William L Edwardson has survived;5. it contains fascinating detail in the form of daily entries for the next three years of the complete voyage. One interesting event recorded was a near calamity! When leaving the port of Rio de Janeiro the Surrey was fired on by the guns of the island fort near the Harbour entrance. The ship was hit on the starboard side and Captain Raine brought the ship to. Raine went ashore and found that in a bureaucratic mix-up by local officials, the fort’s commander had not been advised that the Surrey had been cleared.

On the arrival of the Surrey in Sydney Cove it must have seemed very unusual to note the convicts filing ashore, singing and praising the master and crew who had brought them out to New South Wales. Also, it is not difficult to imagine the sense of satisfaction among the ship’s complement at this gratifying sight. Thanks to the Archives Office of New South Wales, we are able to read a letter dated 25 December 1816 written aboard the Surrey and addressed to Captain of “Surry” – by one of the Convicts, Gerald Hope. Also a longer epistle enclosed with the above letter and addressed to His Excellency, Lachlan Macquarie Esq and signed ‘in the name and on the behalf of all the prisoners by the same Gerald Hope’. In this letter the ship’s officers are thanked including the Purser Mr Winder — none other than our subject, Tom Winder 6

It is probable that a bond was forged between the Captain, Thomas Raine and the Purser, Tom Winder, because history records the friendship which existed between these two men over the ensuing years. In later years in the Hunter Valley as a landholder with assigned convicts in his charge, Tom Winder was known as a firm but fair master inclined to reward good behaviour rather than chastise his servants, a characteristic which he well might have forged from his experience with Thomas Raine in 1816 aboard the Surrey. The Surrey again sailed from Port Jackson on 15th March 1817 on her homeward voyage to England via Batavia.

Here it is reasonable to conjecture on the thoughts of Tom Winder. It is claimed he was a friend of the Governor, Lachlan Macquarie. Having spent a little over two months in Port Jackson, he would have had ample time and opportunity to assess the position in the young Colony. Being of gentle birth but with a lack of incentive to return to England he might have been looked upon as a ‘Remittance Man’. Certainly he was well off financially, and proved to be a capable and astute man of business.

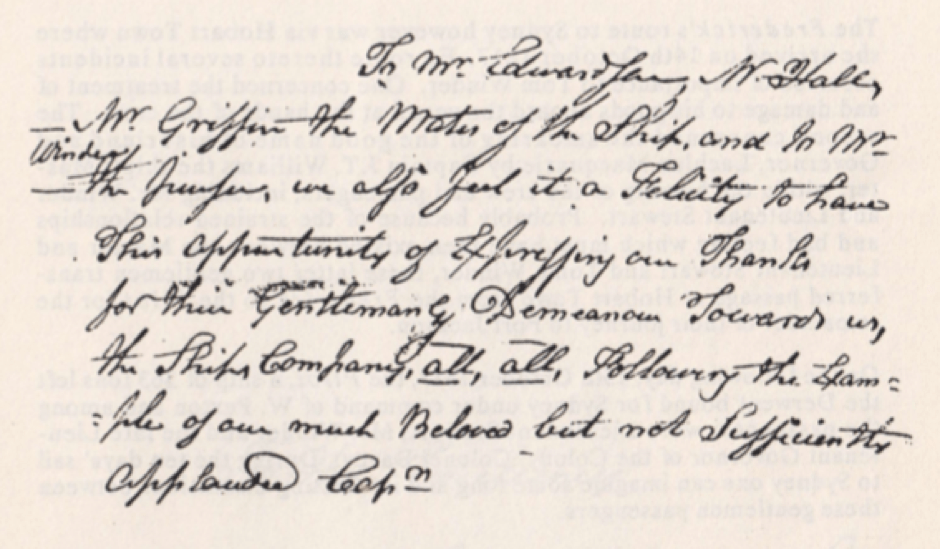

Extract from the letter written “in the Name and on the Behalf of all the prisoners, by Gerald Hope; done on Board the Sussex Decr 1816”:

To Mr Edwardson, Mr Hall,

Mr Griffin the Mate of the Ship, and to Mr

[inserted] Winder the Purser, we also feel it a Felicity to have

this opportunity of expressing our Thanks

for their Gentlemanly Demeanour Towards us,

the Ships Company, all, all, Following the Exam-

ple of our much Beloved but not Sufficiently

Applauded Capn.

The 1817 Voyages of the Frederick and Pilot

We next learn of him shipping a valuable cargo of merchandise from Batavia aboard the ship Frederick, bound for Sydney, via Calcutta, under the command of J T Williams. Tom Winder could have sailed on 15 March 1817, but left the Surrey when she was in Batavia, at about April or May 1817. With the object of purchasing resalable goods for disposal in New South Wales and finding that the ship Frederick was sailing for his desired destination, Winder arranged shipment aboard that vessel for himself and his merchandise back to Sydney.

The Frederick’s route to Sydney however was via Hobart Town where she arrived on 14 October 1817. En route thereto several incidents occurred of importance to Tom Winder. One concerned the treatment of and damage to his goods aboard the vessel at the hands of the crew. The second concerned the smearing of the good name of his friend and Governor, Lachlan Macquarie by Captain JT Williams the ship’s Master, within the hearing of the crew and passengers, including Mr Winder and Lieutenant Stewart. Probably because of the strained relationships and bad feeling which must have then existed between the Master and Lieutenant Stewart and Tome [sic] Winder, these latter two gentlemen transferred passage at Hobart Town from the Frederick to the Pilot for the remainder of their journey to Port Jackson.

On the following day, 15 October 1817, the Pilot, a ship of 363 tons left the Derwent bound for Sydney under command of W Pexton and among the passengers were Lieutenant Stewart, Mr Winder and the late Lieutenant Governor of the Colony, Colonel Davey. During the ten days’ sail to Sydney one can imagine some long and interesting discussions between these gentlemen passengers.

The Pilot entered the Heads of Sydney Harbour on 24 October, almost four weeks ahead of the Frederick, which entered port on 22 November 1817. Tom Winder made legal claim against Captain Williams as Master of the Frederick for damage done to his merchandise, and was subsequently awarded damages of 200 pounds sterling, a large sum of money at that stage. Also, Tom Winder lodged complaint with the Colonial Secretary, JT Campbell Esq, concerning the conduct of Mr. JT Williams “during his passage hither from Calcutta – wantonly and maliciously to asperse the character and ministration of His Excellency Governor Macquarie”.

Conclusion

It seems that Tom White Melville Winder decided at this time to stay in New South Wales and to establish himself as a merchant. He was granted land in Bligh Street where he established a retail outlet for the disposal of his goods. He thus established a new life for himself and his future family in the young Colony, a decision which marked the beginning of along and successful life in this country. More will be told about him and his descendants, and the connections with the Hungerfords, in future issues of this Journal.

Address of Gerald Hope’s Letter to Govr Lachlan Macquarie

Part 2 – The Sydney Merchant

What was this man like? We have no photograph or portrait to show us his physical likeness but we do have material from which we can form a fairly clear idea of his real capabilities and achievements and so we can form a picture of the “man” in our mind’s eye.

Winder is of interest to all those who are descended through his son Thomas and Emily Newell and from his daughters. The eldest, Jessie, married Wakefield Simpson, then three daughters married three sons of Emanuel and Catherine (Loane) Hungerford, namely Ellen and Robert Richard Hungerford, Anne and John Becher Hungerford and Agnes who married William Moore Hungerford. Finally a daughter, Fanny, married Major GJ de Winton. From these marriages there are many descendants in Australia and probably not a few elsewhere.

Miss Essie Lauchland in her report on him described Tom Winder as:

belonging to the cultured classes, fantastically energetic and enterprising. The Hon. Tom White Melville Winder, founder of “Windermere”, Lochinvar in New South Wales moved across life’s canvas in many directions, unostentatiously but very definitely – as trader, winemerchant, storekeeper, mill-owner, partner in business, ship owner, gentleman farmer, magistrate…7

In a previous article of the HAFS Journal we described events leading to Tom Winder establishing himself as a resident of Sydney in 1817. One wonders where he resided immediately upon coming ashore from the ship. Did he stay with friends? Possibly he found accommodation with a boarding establishment owned and (then) operated by Samuel Terry and his wife, for Terry and Tom Winder soon became close friends and were at times, business associates. Torn Winder was one of the executors of Terry’s will. Samuel Terry, a convict, was to become known as The Botany Bay Rothschild as he is said to have been the first millionaire in the young Colony.

Winder’s First Land Grant

A parcel of land (allotment No 14 Sec 44) on the corner of Bligh and Hunter Streets in Sydney was granted to Winder in 1817 as “permissive occupancy”. It was opposite the site of the first church in Australia. Tom Winder used his land to establish a retail/wholesale store and a residence. In May 1820 it was finally granted to Winder. Later it was sold in part of [sic] John McHenry and the major part to Henry Donnison. Donnison mortgaged the land to Samuel Terry who later bought it and then resold it. Donnison was a founder of Gosford and the Tuggerah Lakes District. The land sold by Winder was later to become, in part, the site of the Union Club, the gentleman’s club of Sydney.

During the period 1817-1820 Tom continued to reside at the Bligh/Hunter Streets address, but from May 1819 to March 1820 he visited Calcutta for business reasons. Possibly his decision to undergo an overseas business trip was dictated by an experience involving a deal he and his associates had with a Captain Ritchie in 1818 of which we will learn more a little later.

The Kensington Flour Mill

In 1820, in partnership with Samuel Terry, Tom established Lachlan Flour Mills at Kensington. He advertised the business thus:

I beg to inform bakers and private families that they could receive from the warehouse from that date flour, bran, etc. on the most reasonable terms. The stores are always open for the reception of wheat.

By December 1820 Winder advertised for a superintendent to manage the flour mills and he states:

None need apply but those who can write, have a clear knowledge of millering, and can bring testimonials of honesty, sobriety and industry, as liberal encouragement will be given.

Winder was about to make another overseas buying voyage. In 1820 Winder and Terry entered into an extended partnership with William Hutchinson, Daniel Cooper, George Williams and William Laverton, and renamed the Mill the Lachlan and Waterloo Flour Mills. The partnership actually traded as Hutchinson, Terry & Co.

The owner of the land on which the mill was built needs further examination. It seems to have belonged to Terry for he was granted 570 acres there. Certainly the Lachlan Mill Farm existed prior to the grant to Winder of 417 acres adjacent to this (Kensington) Farm.

Was Some of the Flour Rotten?

It is of interest here to note that the milling undertaking was not without opposition. A John Dickson had established a steam mill in the vicinity of Darling Harbour on land granted by the Governor. There were also many other mills operating. Hutchinson, Terry & Co apparently under-cut Dickson’s price to obtain Government contracts. It was claimed that the contracts granted were never advertised.8

Gwyneth Dow in her excellent book on the life of Samuel Terry says that Dickson claimed the negotiations had been “fraught with collusion”. On the other hand Hutchinson, Terry & Co were of the opinion that they had offered to do the work at a loss to protect the Authorities from the “exorbitant charges” of earlier contracts.9

In Dickson’s appeal he points out that he had come to the Colony, an experienced miller and free, whereas his opponents had brought nothing except “in the shape of fetters”. Dickson undoubtedly had good grounds for complaint, since the new contractors were henceforth granted a contract at the increased figure of nine pence per bushel ground instead of the former price of one penny.

Winder’s Deed of Grant was dated 27 May 1823 but his shares in the partnership had been sold in February of that year. Was there something awry? Perhaps Tom Winder felt that the business was lacking in proper supervision for there were several well executed forgeries detected in the firm’s one and two denomination notes during 1822. There is also the possibility that since Winder was the free and respected gentleman in the undertaking and was the personal friend of the Governor he may have wished to be free from the shadow of involvement. It was the period of strong feeling between the forces of Emancipation and Exclusionism…

Winder’s Land and Property

Winder’s land is now the location of the Lakes Golf Course as well as parts of the Sydney suburbs of Eastlakes, Daceyville and Pagewood. Roughly it extended south from Gardiner’s Road to Wentworth Avenue, on the west to St Helena Parade and the east to Banks Avenue. The present Southern Cross Drive cuts north to south across the middle of the allotment. Terry’s land is north of Gardiner’s Road and is now the location of the suburb of Kensington.

Winder had other interests in the properties of the young settlement. He was granted a small parcel of land of what is now Bankstown. In 1820 he advertised that he was selling a dwelling house with furniture, goods, chattels and effects belonging to one Japhet White at Liverpool. Another property, later to be of considerable value, had been purchased from Underwood and consisted of several parcels of land in the area which is immediately north of the railway line and extending from Summer Hill to Ashfield. These grants had been given initially to retiring military personnel and others. One large parcel had been granted to Henry Kable.

Tom Winder advertised the sale of this land at Long Cov, four miles from Sydney, on 29 March 1822.10

It was then 175 acres. The Underwoods repurchased the land and eventually in the 1870s it was subdivided into its present format. Liz Parkinson in her very comprehensive research has produced a fine written and illustrated book covering their history. 11

Tom Winder and Ellen Johns(t)on(e)

Several histories of the time state that Winder married in 1818 Ellen Johnstone, but registration at the time was not compulsory, and it is more likely that they followed the practice of many others who took a partner and vowed allegiance for life. Harry Boyle, the historian of Hinton in the Hunter Valley, states that this vow was commonly made under a tree or beside water. Whatever the facts are, we know that the arrangement was not performed at the time under church or state law.

In 1818 or 1819 this couple had their first child, a girl Jessie. The mother Ellen Johnstone (sometimes Johnson or Johnston), who was employed by Tom Winder in his Bligh Street premises, had three children by the time of the 1822 General Muster. In this these children are recorded as having Johnstone as their surname, but in later census documents they are listed under “Winder”. Actually Tom and Ellen did not church their marriage until 26 December 1848 at St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church in George Street, Sydney (adjacent to the present St Andrew’s Cathedral). Neighbours from the Hunter River District, Mary White Dun and Thomas Dun, and also Edward Wakefield Simpson12, were witnesses to the marriage which was performed by Special Licence issued by the Governor. By that time, Tom and Ellen had had nine children.

Tom Winder in Public Controversy

In this mercantile period of Tom Winder’s residence and activity in Sydney he was prominent in public affairs. His signature can be found alongside of those of William Wentworth, John Macarthur and others on a number of Memorials/Petitions to the Governor. He was selected by Samuel Terry to arbitrate in a major commercial dispute concerning a distillery in Paddington in 1824 and with Daniel Cooper.

In 1818 Tom Winder was also involved in another public commercial dispute. He had become involved in a speculative trading venture with Samuel Terry, Robert Campbell Jnr, Thomas Wright and Joseph Underwood. They drew up an Agreement with Captain Ritchie of the ship Greyhound in June 1818 to put up ten thousand pounds for cargo to be brought from India. Ritchie tricked the merchants by unloading the cargo on his return at Hobart, where he sold it. Ritchie claimed, “his vessel being found on survey, unsafe from a leak which was irreparable there the cargo was sold as partially damaged”. The goods actually arrived in Port Jackson aboard our old friend, the ship Surrey on the same day as the Greyhound reached port.

Captain Ritchie claimed the agreed bond allowed his action as the goods were to be delivered, “the dangers of sea excepted”. The goods were subsequently shipped to Sydney by the firm Riley & Jones. Terry and his friends took the matter to the Supreme Court in Sydney in June 1819. Justice Field allowed them only one farthing damages. An appeal failed. This decision may have reflected a hostility to emancipist merchants.

Tom Winder was in the headlines again in the press of the day when in 1821 his Bligh Street storehouse was robbed in a rather unusual but effective fashion. A pipe of Jamaica Rum was stored close to the wall which was built of brick. The wall was bored through with a bit and a tube inserted, through which nearly all the contents of the pipe were drawn off. A periodical of the day records the comment:

We have had many previous instances of caution against depending on brick walls for storage in shops, but where a store is already built it would be wise to have a lining of stone built to a secure height.

Although Tom Winder was clearly associated with, and was accepted by the “establishment” in Sydney at the time, including some of “the pure merinos” as they were called, he freely entered into friendships and partnerships with emancipated convicts (Terry, Hutchinson and Underwood) and the sons of former convicts (William Charles Wentworth). Perhaps Tom Winder’s partner (and later his wife) Ellen, free-born in the Colony – a Currency Lass – was a daughter of a woman who had been a convict. We do not yet know the facts in this regard. Ellen’s father, who had apparently died early, was a soldier named Lester.13 Did such a connection with his experiences aboard the Surrey with Thomas Raine influence Tom Winder’s attitudes? He appears to have gained respect from all those persons he had dealt with from the convicts assigned to him right up to the level of Governor.

The Next Chapter

By 1821 Winder had grown pessimistic about the future profit from mercantile undertaking in Sydney and he therefore turned his attention to other fields of endeavour of which we shall hear more later.

Part 3 – 1821: Change of Direction

Tom White Melville Winder, the man of success in business and landed interests in Sydney was unsettled as well as despondent about the future business trends in Sydney. The period of his stay in the young colony since his arrival at the beginning of 1817 was one of great difficulty.

Hard Times around 1820

The economic instability during the years of Governor Macquarie resulted in a long and serious depression and Tom Winder, coming towards the close of this difficult time, nevertheless survived and indeed prospered.

As Gwyneth Dow points out in her book on the life of Samuel Terry:

with many men who had earlier speculated in trade, either went under or withdrew into safer ventures, a small crop of dominant merchants survived, owing their of the colonial market. By 1821, these were Jones and Riley, Berry and Wollstonecraft, Robert Campbell Sr., Prosper de Mestre, Winder, James and Joseph Underwood, and of course Terry, a fair sample of both free and freed. Their success came not only from careful predictions, but also from having the capital to withhold supplies and credit until a favourable moment on the market.

In his report in the Sydney Trader at the time, Hainsworth reports that the big men tended to specialize more and more by the end of Macquarie’s time (1810-1821). Hannibal Macarthur bitterly observed that a man could be a merchant or a farmer but not both. Hainsworth observes that the Macarthurs turned to grazing, Simeon Lord, Underwood and Winder to manufacturing. But this was not so clear cut, in Winder’s case the occupation probably referred to his milling interests.

Following these depression years a further crisis hit the colony, in the form of disastrous floods, as well as an influx of convicts and free men following the end of the Napoleonic Wars. This all assisted in creating a labour problem.

Tom Winder’s Letter to the Governor

Tom Winder, on 9 June 1820, wrote a letter to the Governor. From this letter Winder’s decision to leave Sydney and change his occupation to farming is noted. He uses the quaint wording and address of the time.

Sydney June 9 1820

In the course of the current week, I have, on three different days, done myself the honor of calling at Government House, for the purpose of soliciting the indulgence of an audience before your Excellency.

In each instance, however, I lament to have found, that, in consequence of your Excellency’s numerous and important avocations, I have failed of receiving the solicited honour.

I now therefore do myself the honour to detail, in writing, the substance of that communication, which I have been so anxious to make, in person, to your Excellency and to solicit for it your Excellency’s convenient and favorable consideration.

The present impropitious or rather disastrous condition of the Commerce of this Colony is, I apprehend, not unknown to your Excellency, nor need I intimate to your Excellency, that this depressed and even disastrous state of our Commerce has resulted from events, which neither prudence nor ordinary foresight could reasonably anticipate, a sudden unexpected and inadequately extensive influx of Merchandise into a confined Market.

I left the Colony for Calcutta in the month of May 1819 whence I arrived again in this Port with a Cargo of sundries, in March last, 1820.

This adventure, under the existing circumstances of an overcharged Market here, has not been merely unprofitable, but independently of lost time, it has been attended with my considerable pecuniary loss.

Under these circumstances I have deemed it matter of wise and prudent consideration to withdraw forthwith the whole or the greater part of my funds from Mercantile, and to employ them in other pursuits, more advantageous, or at least more promising.

With this view I propose to myself the erection of a Water Mill for the making and dressing of Flour, in the vicinity of Sydney.

To this project I have been led by two important considerations. First, that a vacant spot, sufficiently adapted to the object at this moment presents itself.

Secondly, that from the present insufficiency of Mills to the exigencies of the Colonists, not only here, but in Van Diemen’s Land, the erection of another cannot be deemed otherwise than as equally conducive to the interests of the proprietor and those of the Community.

The spot, to which I allude, is situate about half a mile from Mr.J. Hutchinson’s Mill on a small stream. This spot, useless by nature for any other purpose, combines in it numerous and most important advantages for my present plan.

By the erection of a Mill on this stream, I propose, not merely to contribute considerably towards providing flour for our rapidly increasing population, but to rear, contiguously to the Mill, a large number of Hogs, to which the ground is particularly adapted, and with the offal of the mill to fatten them for the market, or for being salted down.

To Your Excellence, I trust, my latter object will appear of the highest importance at a time, when, from our increasing population, and the casualties of our climate, a sufficient supply of animal food and that of inferior quality, is with difficulty procurable for the use of His Majesty’s Magazines.

The above I submit as a bare outline. Should your Excellency be pleased to bestow on it your indulgent and favorable consideration, I shall do myself the honour again to trespass on your Excellency by stating the nature and extent of assistance from Government which may appear adequate to the accomplishment of my proposed object, or such as Your Excellency may feel disposed to consider the peculiar ends of my project and my individual circumstances to merit.

I have the honor to be

Sir

our most obedient Servant

TWM Winder

Winder’s Motives for the Change

One is inclined to wonder if there was not another more personal reason for this decision. As a friend of the Governor, and being implicated heavily with men of convict background, Winder could conceivably have been advised by his influential friend to extricate himself from his involvement in milling and accept a change of life elsewhere.

At this time there was great friction, even enmity, between the Emancipists and Exclusionists. Winder belonged to neither camp. Land in the Coal River (Hunter) had been up till this time reserved against allocation to settlers, in order to preserve the isolation of the reconvicted felons quartered in the gaol at Newcastle, and also to confine to a degree the lean settlement being established beyond the Great Divide and in the South.

The Hunter Valley acreages had largely been cleared of cedar and rosewood, disclosing some very fertile-areas of farming land. Furthermore, the coal deposits at the mouth of the river were available for development through private enterprise. Perhaps therefore the conjecture of Winder being “tipped off” may have some substance.

A factor which would have influenced his decision was his interest in shipping. The landed route to the North beyond Wiseman’s Ferry was notoriously difficult, as Winder himself was to find later on when his stockman was to lose some cattle which had been dispatched on the overland route through Wollombi. Only 70 nautical miles north of Port Jackson lay the entrance to the Hunter River, in reasonable weather a preferable route, which would have appealed to the eye of a businessman with shipping interests.

Winder’s Reward

Whatever the reason, Winder’s die had been cast, as he was immediately rewarded by the allocation of a fine grant of about 700 acres of land, it being one of the first made other than to selected freed convicts from the local gaol.

As early as 27 October 1821 Winder had addressed a reminder letter to the Governor, seeking a land grant to graze cattle and “in order to further his objects” in an agricultural undertaking. Three days later, on 30 October 1821, the Governor approved the grant, with the allocation of three Government men, all convicts, for six months on Government stores, the date to commence when Winder took possession of his land.At this time he states his capital in the colony exceeded 7000pounds sterling. Here is the letter and its confirmation:

Bligh Street Sydney

I beg leave to avail myself of the present opportunity to state to your Excellency that I had the honor of addressing a Memorial to you some time since soliciting the Indulgence of a Grant of Land as a Settler for the purpose of grazing my Cattle and furthering such general objects as I might have in view in agricultural pursuits.

Not having received any communication from your Excellency on this subject I take the liberty in reference to that Memorial to solicit a compliance with the prayer of it and respectfully to inform your Excellency, that my capital in this colony in money and property at this time exceeds seven thousand pounds sterling, and that my returns in a commercial point of view have not only added considerably to the business, but contributed to the general accommodation of this Inhabitants of the Colony.

I have the honor to be

Sir

Your Excellency’s very Obedient Servant,

T W M Winder.

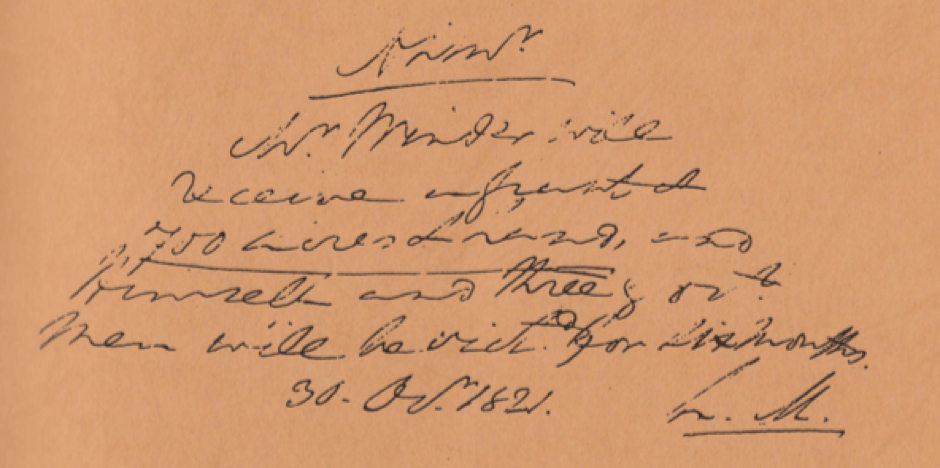

[Note on reverse side of letter by Lachlan Macquarie:]

Mr Winder will receive a grant of 700 acres of land, and himself

and three govt men will be vict’d for six months. 30 Oct 1821

LM

- Mr Palgrave Carr lived at Narrabeen; his wife is Jean (Tyrrell) Carr.

- Editor’s note: The Convict Ships, p 177 locates this at Shoalhaven, and notes that ‘there was now nobody to navigate the ship”, hence the volunteer‘s transfer.

- Editor’s note: The Convict Ships p 178 explains that an enquiry was held, finding that the Master and Surgeon were to blame for the debacle. 240 gallons of wine put on board for the convicts was missing: this was normally issued regularly as an anti-scorbutic. The usual death rate among convicts on voyages at this time was 1:90; on the Surrey’s 1814 voyage it was 1:9.

- Editor’s note: Gerald Hope’s letter notes that two missionaries (the Revs JM Orsmond and C Bars (Barff?)) travelled on the ship. and were largely responsible for this work. as also of eliminating blasphemy!

- Log of William L Edwardson. Chief Officer of the Surrey (Surry), Mitchell Library REP PRO 87 I-10.11/2 pp 129-139.

- Editor’s note: the portion of the letter mentioning Tom Winder is reproduced here with permission of the Archives’ Office; interestingly the name has been added in a later editing of the handwritten letter.

- ES Lauchland The Story of the Founder of Windermere, 1948

- Court of Appeals, NSW Archives Office 2/8142.

- Gwyneth M Dow Samuel Terry-The Botany Bay Rothschild, Sydney University Press 1974

- Sydney Gazette, 29 March 1822

- Liz Parkinson The Underwoods – Lock, Stock and Barrel, The Lazy Lizard.

- Edward Wakefield Simpson was a son of Wakefield Simpson by a former marriage in England. Wakefield, a widower, was to marry Jessie Winder in 1836

- Information from Ellen Winder’s death certificate, 29 January 1887

- Courtesy of the NSW Archives Office Reel 6049 4/1744, pp 360-3

- Courtesy of the NSW Archives Office